Biography:

Biography:

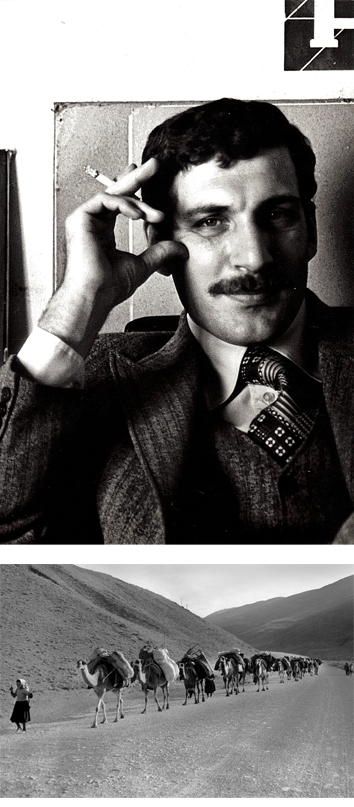

Erdal Küpeli was born in Malatya in 1945. Küpeli completed his primary and high school education in Malatya and graduated from the Master Architecture Department of Istanbul Fine Arts Academy of the State in 1972. He has actively worked in the establishment of the Turkish Film Archives (now the Cinema and Television Research Center), which provides trainings and carries out researches. In 1967, together with a group composed of student friends, he has established the Turkish Folk Arts Research Association and made researches on local and traditional architecture, ethnographic materials and handicrafts in East Black Sea, South West Anatolia, Central Anatolia, East Anatolia regions and documented them. He has exhibited those works with 10 different exhibitions between 1968 and 1972 at the exhibition halls of Istanbul Fine Arts Academy of the State, Architecture Faculty of Istanbul Technical University, Yapı ve Kredi Bank Istanbul and Ankara exhibition halls. Between the years 1976-1982 he has given photography lessons to students of School of Applied Industrial Arts Graphic Arts Department. In 1982 he was assigned as a lecturer to Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University Photography Department. Between the years 1987-1989 he worked as the General Secretary of Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University. In 1990 he was appointed as Associate Professor to the Photography Department. He has been the Chairman of the Documentary Photography Art Branch at the same department. He has retired in 2005 from the same position.

Küpeli still continues to work as a freelance architect and a photographer in Antalya.

Exhibition: Immigrants

In 1968, we had found as students an association named “Turkish Folk Arts Research Association” as part of the student activities of Istanbul State Academy of Fine Arts. Our goal was to research the extant verbal-written materials still being used within the borders of the Republic of Turkey after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, and share the findings and documents with people through exhibitions, publications and various other ways.

Within the scope of this study, we conducted many studies in various regions of the country between 1968 and 1972. All of us were students and we had no way to finance this research. The director of Yapı Kredi Bank Culture department, Vedat Nedim Tör, and a minister of the late Democrat Party regime, Şemi Ergin, who assumed the same office after Vedat Nedim Tör’s death have made prepayments in amounts varying from 1000 to 2000 liras for each trip we had to make and help cover the expenses of exhibitions. 5-6 people attended each trip and each trip lasted around 25 days. Everywhere we went, local officials did everything in their power to help us out. In particular, the forest agency helps us reach the highlands and hamlets. Often times, we slept in yoruk tents in the villages and ate with them. Our team had a limited number of cameras on our hands.

Our first trip was to the Eastern Black Sea Region. We studied in a wide area starting from Ordu and extending until the Fındıklı district of Rize. Our next trip was to the cities of Antalya, Isparta and Burdur to study the yoruks who were carrying on the nomadic traditions. We lived with yoruks for a week on the highlands of Amanos. The following year, part of the group went to the Southeastern Anatolia and Van Lake while another went to the cities of Rize and Artvin to continue our studies. We worked with the Kurdish nomads living in the crater on Mount Nemrut. In 1971, we conducted two different studies; on in rural areas around Sivas-Yozgat, the other in Urfa-Harran. Lastly, we worked around the cities of Niğde-Kayseri-Malatya of Central Anatolia, migrated alongside yoruks of the Pınarbaşı district of Kayseri, and lived among the Turkmen clans of the lowlands of Bor.

Yoruks generally live in black tents woven from goat hair. All preparation for the migration is done by women. After all the necessary items (mattresses, cushions, rugs, all kinds of kitchenware, wool cropping-spinning, roving, and yarn dyeing equipment, weaving machines, cookers, and equipment used to transport water etc.) are put in sacks and loaded on camels; they hit the road. Almost all of these tasks are performed by the women. Tents are erected and set up by the women so that they are habitable. Generally it is the children, both boys and girls, who deal with the grazing of the herd. Daily tasks such as milking the animals, making yogurt and cheese, extracting fat, cooking, shearing the sheep, wool spinning, roving, yarn dyeing, and weaving are all done by the women. Men sometimes help but their primary duty is to provide and ensure security.

During the period we lived together with yoruks, we made drawings and took photos of their equipment, their fabrics (rugs, light rugs, sacks etc.) and patterns in their fabrics. We learned the names of the fabric and the patterns, recorded the folk songs and stories about them.

Today, when I look back on this work, I realize how important photography is against the loss of cultural values.

There is still much to be done and we need passionate volunteers for this as for all the other fields. I would like to think and hope, on my part, that they exist.

This post is also available in: Turkish

English

English Türkçe

Türkçe